Safety Isn’t the Absence of Danger — It’s the Presence of Connection

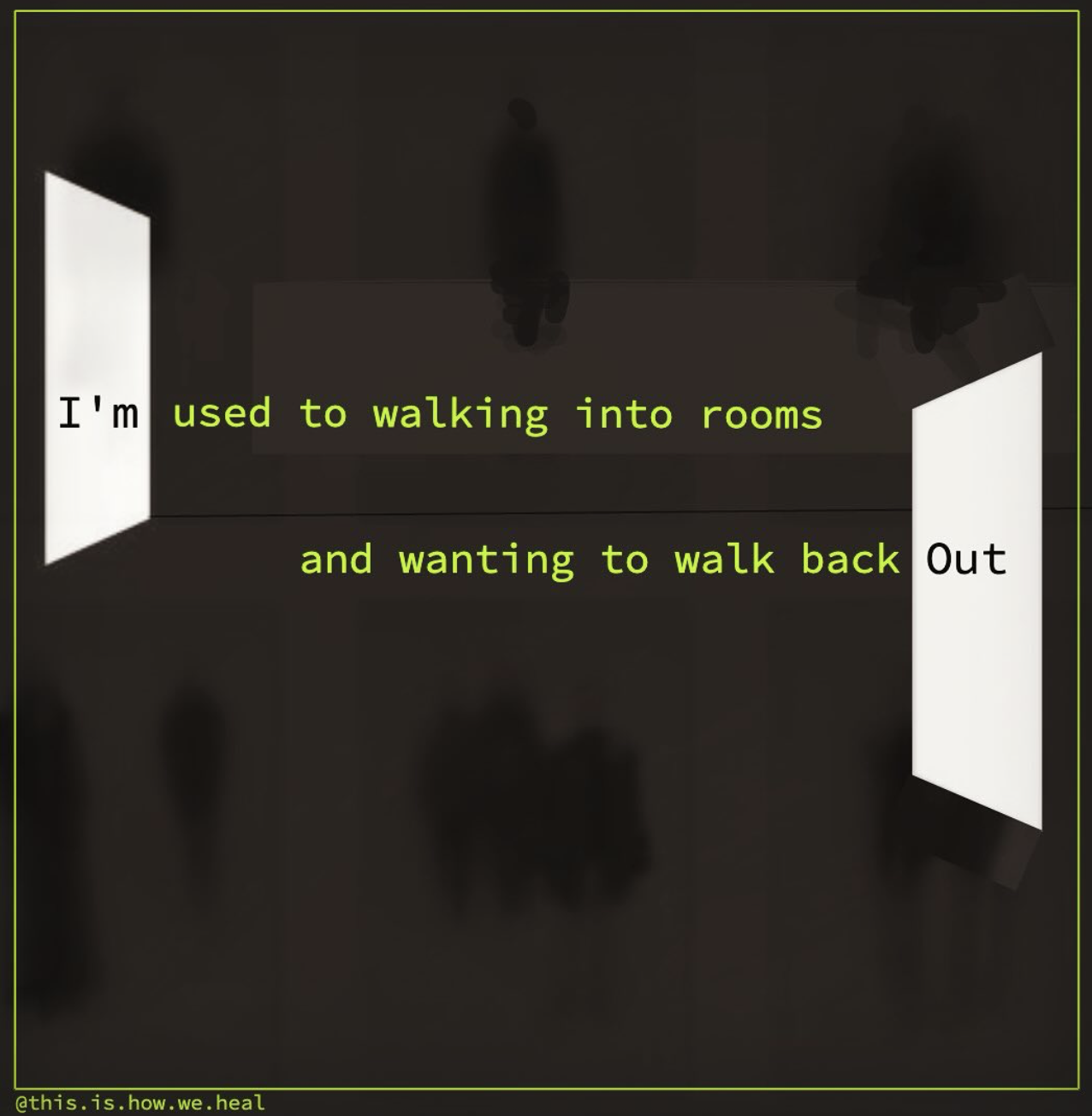

I used to walk into rooms and immediately want to walk back out.

In the entertainment world, I spent years attending events—opening nights, media interviews, post-show parties, sponsor meet-and-greets. I’d shake hands, smile, banter, sell the show, sell myself.

People assumed I loved it.

And I was good at it—performers usually are.

But walking into those rooms often made me want to turn around and leave. If you’ve ever felt that particular hollowness in your gut, the way your breath goes shallow and your body tenses like it’s quietly bracing... you’ll know. It’s not about the people in the room. It’s about not feeling safe in it. And my very first thought? A wine. A red. A big one. (Like a prop. But for my nervous system.)

And then—every now and then—someone shows up. Not a best friend, just someone you super vibe with. Easy to talk to. You enjoy being around them. Suddenly your system shifts. Your breath returns. You laugh. You land. You might even find yourself softening into your environment.

I once read about US war veterans whose bodies started associating safety not with being away from war—but with being beside the people who went through it with them. Coming home, for some, felt more disorienting than comforting. Because the people who made them feel safe weren’t home.

Gabor Maté said, “Safety is not just the absence of danger. It’s the presence of connection.”

I think about that a lot in my grief work.

Sometimes, in grief, what we long for isn’t to be fixed.

It’s just to have our grief seen—by someone who helps our body feel safe enough to stay.

If you found this post helpful, feel free to share it with someone who might benefit!

Warmly,

George Chan

This Is How We Heal

George Chan, MCOU, is a Counsellor, Grief Educator and Breathwork Coach who specialises in helping individuals navigate grief and loss through his private practice, This Is How We Heal. With a rich background in theatre and entertainment, George brings creativity and empathy to his work. When he's not in the therapy room, you might find him performing, choreographing, or working on a new production—or spending time with Luna, his Jack Russell Terrier, who doubles as his unofficial co-therapist and production critic.